[Note from Christopher: While writing my novel Robbers, I fell in love with one of the characters in it—a coonhound named Lefty. So when the novel was finished, I looked around and found myself a new friend, a Treeing Walker hound just like Lefty. His name was Buddy. At least that’s what I called him because his “official” name on his papers seemed a tad pretentious, as such names often do. It was “Magnificent Thunder III” or some such silly thing. Anyway, I took Buddy hunting in East Texas and wrote about the experience for the February 2001 issue of Texas Co-op Power Magazine. Later, when I moved to Prague, Czech Republic, I had to find Buddy another home. There aren’t many coons in Central Europe, and I didn’t think he’d enjoy living in a big city. I reckon he appreciated his new country home in those East Texas piney woods more.]

It’s dark in the woods, nearing midnight, and cold. The four of us sit under a camp light hooked to a 12-volt battery, trading tales and listening to the hounds. They’re off in the distance, a dozen of them, trailing fox or coyote. The rowdy sound of the chase—high-yelping bitches, several low, hoarse-mouthed males—ricochets off tree trunks, comes snaking through the thicket.

It’s the symphony of sound that we came to hear.

We arrived in these East Texas woods just north of Jasper, near Indian Creek, in the early late autumn evening. We drove along an endless, curving dirt lane off the blacktop until we reached the camp. “We” being J.W. Adams and his younger brother Alton, John Cooley and myself, and the dogs.

After setting the dogs loose, we set up the light and unfolded chairs in a circle. Poured hot coffee from a thermos and settled in for another night of listening to the hounds run, a weekly ritual for these men. It seems like we’re a thousand miles from anywhere. Above, stars glitter through a canopy of trees. From the darkness below come nightbird calls and the thrumming of insects—and a mouthing chorus of hounds.

During the course of the evening, the conversation has ranged as far and wide as the dogs have. We’ve touched on waterwitching (consensus: it works), the food value of watermelons, legendary high school football teams, trade unions, and how to catch alligators (big hook and a dead chicken).

Now Alton, 70, pauses during a discourse on how his daddy, who worked for Kirby Lumber in Roganville, got paid in “white horse” scrip only good at the company commissary. He tilts his head, listening, then observes, “That’s ol’ Buck. I better trim his toenails a little shorter.”

We all fall silent and heed the dogs for a bit, then older brother J.W., 78, recollects a story. It seems two men were in the woods listening to the hounds run and one exclaimed, “Man, listen to that music!” The other fellow, a novice, cocked an ear and frowned, then replied, “I can’t hear nuthin for all them damn dogs.”

Alton chuckles and John Cooley, a comparative youngster at 63, smiles. That’s a pretty strong response from John, a man not known to run a loose mouth. In fact, John is so reluctant to waste words that he doesn’t name his dogs. He’s content to refer to “that red dog” or “the little gyp” and let it go at that. He did once have a dog he called “Hard to Catch,” but the reason for that name seems self-evident.

Running dogs doesn’t seem to attract young men like it once did. Maybe the younger fellows are busy elsewhere with more important matters, but I suspect something else has happened. My hunch is that listening to hounds trail a scent through the deep woods—not even for prey, but simply for the thrill, as we are doing—is a frontier tradition that is slowly disappearing in East Texas, like making your own mayhaw jelly or canning your own crowder peas. So as I sit sipping coffee with these men, I sense that I’ve been invited to share an avocation not long for this world.

My thoughts are interrupted when the talk suddenly turns to lightning. J.W. asks if lightning damages timber when it strikes. Alton replies, “Not pine. But cypress now, you saw it and you won’t notice anything. But put it in a planer and you’ll see hairline fractures all through that wood.”

We all nod at this news, consider its ramifications for the timber industry, then the discussion moves on to the genealogy of dogs. As the night has progressed, I’ve learned the two subjects of conversation we inevitably return to again and again are the genealogy of dogs and the genealogy of people. For instance, an exchange might go like this:

“Did he come out of Donna?”

“No, but Chub did.”

“Chub come out of Donna?”

“Yep.”

That’s in reference to dogs. A discussion of people can sound roughly similar, though in them you’ll often find mention of issues of health, as when J.W. says, “Ol’ Earl went over to Houston and they punched a hole in his heart. Now he’s doing good. He sure has lost the weight. His brother Charles has got big as a bale of hay.”

And in such a low-key manner does the news essential to long-time friendship in a tight-knit community make its way from person to person in the countryside and small towns. Of course, these news items eke out slowly through the night, in bits and pieces, subsidiary to lending an ear to the dogs. At any moment, a change in the euphony of hounds will stop a conversation cold.

“That’s Hammer,” comments J.W., cutting short a story from Alton about eating a loggerhead turtle, which didn’t taste all that bad. (“I’ve eaten a lot of things,” he adds, “but I never ate no snake.”) Hammer is the son of Jackhammer and has a strong, clear voice, spine-tingling to hear. J.W. clearly puts thought into the naming of his dogs. His bitch Reva is named for a character on the TV show A Guiding Light. Mary Lou is named for Mary Lou Retton, the Olympic gymnast. After a minute, as if speaking to himself, he adds, “I didn’t bring Drusilla.”

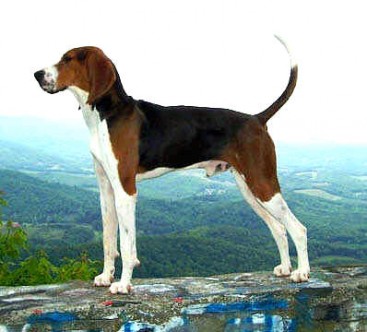

When asked how long he’s been running dogs, John Cooley says, “Since I was in grade school. All my life.” In that time he’s owned hundreds of dogs, spent a thousand nights in the woods with them. The ones he owns now he calls “lemon-spotted Walkers.”

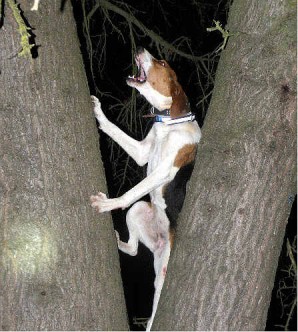

Along with black and tans, blueticks and redbones, Treeing Walkers are classic tracking hounds. Put your finger on a surface and two weeks later a hound can still detect your scent on it. Ground that is too dry or too wet won’t hold a scent long, but if a scent is there a good hound will catch it.

John’s lemon-spotted Walkers are small and run low to the ground, a good match for threading East Texas thickets. My dog Buddy is a tall, long-legged Walker from Arizona. I bought him from a fellow whose wife had offered an ultimatum: fewer dogs or one less wife. He managed to part with one. To his wife’s credit, she saw the suffering she’d caused and let him keep the rest.

But I haven’t put Buddy on the trail in more than a year, and it shows. He appears to have made a career change from working hound to pet. He’s here tonight, and while the other men’s dogs are out there in the woods mouthing and yelling, Buddy is lurking around the camp like a house dog. It’s embarrassing.

“Well, he’s a good-looking dog,” J.W. finally offers, and the words cut to the quick. It’s true, but that’s like telling a fellow with a broke-down car that its paint job looks real pretty.

“He was trained on coon,” I observe, “he ain’t used to running fox or coyotes,” and the others nod agreement. At least I think they nod. Secretly, I suspect they’re of the mind Buddy wouldn’t notice coon scent if the coon was astride his back. And I’m not sure but that I don’t I agree. He sure is acting like a lapdog, loitering near in the light as if someone might offer him a piece of ham sandwich.

Irritated, I call Buddy and stride off down a trail into the woods and leave him there with instructions: “Join that pack of hounds, hoss—and I mean it.” Then I return to the camp and listen for Buddy’s deep-chested voice.

Alton is mid-stream describing how a gray fox circles in a chase while a red fox runs back and forth. “Them red foxes stink to high heaven,” he adds. “They stink like a skunk.”

That observation prompts recollection of Ol’ Bob, a bob-tailed hound that liked to kill and eat skunks. Everyone is agreeing that there’s nothing worse than hauling home a dog that killed a skunk when I glance up and see Buddy hanging uneasily at the light’s edge. He sees me watching and slinks in, looking ashamed. As well he might.

But the other men pay no attention and the conversation turns to Uncle Frank Sylvester of Kirbyville, a World War I veteran who voted early in the November election, just in case. After all, he’s 113 years old. Or 114, or 117. No one knows.

“Tell you another thing,” Alton says, “no matter what Uncle Frank says, no one can dispute it.”

That statement meets another unanimous consent but before a new subject is broached the hounds draw near and we all fall silent, listening.

The dogs let loose in full pursuit, yapping and yelping and bawling in the deep, dark woods. The sweet symphony of sound rises as if on beating wings, conducted by nothing but ancient longings for the chase.

*****