[Note from Christopher: Almost everyone loves to eat shrimp. But somebody has to catch them first… and catching shrimp is hard work. I grew up watching shrimp boats work the bays and shallow offshore waters along the Upper Texas Gulf Coast. I always wanted to go out on one of those boats. Then I finally realized the easiest way to do that was to get a magazine to pay me for a story on shrimpers and shrimping. In 2003, Texas Co-op Power Magazine agreed to do just that. So I spent several days with shrimper Mark Gilbert on Galveston Bay. This is the article I wrote. My thanks to the magazine for letting me re-publish it here.]

An hour before dawn, the time of deepest silence, when all the world still seems to be dreaming, Mark Gilbert is down in his engine room among the grease with a wrench adjusting valves, checking gears, wiring, oil. The yellow glow of his work light creeps up the ladder, falls over the moist deck, casts the winch and ropes looped over pin rails in flickering shadow.

Overhead, beyond the upstretched outriggers, low coastal clouds chase a glossy half-moon past stars over the Bolivar Peninsula. A warm southeast breeze carries the salty tang of sea, of surrounding bay and fertile marsh, of rank organic decay procreating new life.

With a quick jab, Gilbert punches the starter button on the wall and the V-6 diesel growls, grumbles, awakens. The deck of the Stingaree 2 vibrates, the low rumble rolls over the dark water, and Gilbert comes up the ladder wiping his hands on a towel, an expression of satisfaction on his face. Time to undo the mooring lines. Time to hit the bay.

Time to chase those shrimp.

***

Gilbert has been pursuing mudbugs since he was a boy. His father was a shrimper, and so was his grandfather. In the pilot house, he lights a cigarette and sips black coffee, reflects for a moment on his own life at age 42. No benefits, no retirement, imports pushing down shrimp prices, fuel costs rising, eternal boat maintenance, state regs in chronic flux, hard labor, long hours, blazing summer heat, starving to death in wintertime. And unpredictable shrimp.

Otherwise, it’s a cushy occupation.

Gilbert laughs loudly, a machine gun discharge, a cheerful affirmation of life’s small ironies. Then, as if summing up, adds, “Only you don’t have to kiss nobody’s ass like on a 9-to-5 job.”

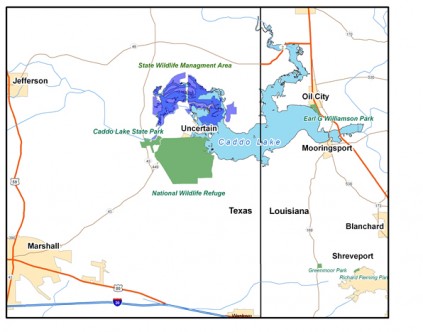

He hits the throttle, turns the wheel. The 40-foot trawler advances slowly along the narrow canal past darkened dockside homes on pilings and covered boat stalls, past the Stingaree Marina with its boat ramps and bait shed—all silent, not even the first gull’s cry of a new day yet—then crosses the Intracoastal Waterway, heading north through a slender cut past Goat Island into open water, the shallow East Bay.

The bay, with an average depth of only two to six feet, is part of greater Galveston Bay, the northernmost in a series of five major bay systems along the 400-mile arc of Texas Gulf coastline. The bays, along with their barrier islands and marshes and wetlands, form complex estuarine systems where fresh river water meets sea water. The commingling creates a salinity gradient influenced by upland droughts and floods, and by how much precious river water is removed upstream by people: city dwellers, farmers, industries. That, in turn, determines the quality and quantity of thousands of species of marine life that breed and grow in the fecund estuaries. Too little fresh water flowing in and the bay ecosystems will collapse. If that happens, then no more shrimp, no oysters, no crabs, no more… well, the intricate web of nature is woven tight, and the consequences much larger than just the bays.

Gilbert nudges the wheel, gazes eastward. The sky is breaking open with a rosy flush of dawn over the marsh. The first black-headed laughing gulls whip past, then several brown pelicans gliding in close formation over the surface, enormous bills thrust forward. Pesticides almost drove these regal birds to recent extinction. Now on the rebound, they are still listed as threatened.

The wind has shifted and picks up, the waves on the bay are becoming choppy, churning the water, a condition Gilbert prefers. “I like it rough and muddy,” he observes. “When the water’s clear, shrimp can see the net coming. They scoot away.”

He falls silent and slows the boat, one eye glued to the depthfinder perched on the dash next to his GPS. Moments later, he explains his worry. The bottom in here is especially shallow since last winter when a drilling company pushed two rigs several miles up East Bay to Frozen Point.

“They needed eight feet of draft but had three feet of water. They plowed up the bottom. Destroyed two acres of oyster beds, left a hill of mud down each side of a false channel. And never came back to clean it up. Seems like there’d be a law.”

Did they find oil?

“Naw, they didn’t.” He shrugs, in no mood now for laughter, and guns the throttle, rotating the wheel to bear west toward Hannas Reef and Port Bolivar, about six miles away, where East Bay opens into the main bay.

“Let’s go for deeper water.”

Gilbert is a short, sturdy man with a beard permanently trimmed in a three-day growth, his head hair cut to a gray burr. His skin is sun-burnished, wind-whipped, his keen eyes crinkled from the relentless bright light. His gimmee cap reads: Commercial Fisherman, Endangered Species. He does not think his own son, Patrick, will become a shrimper. Or his daughter, Claudia.

Nor does he want them to.

***

Half an hour later, Gilbert steps onto the back deck and lowers the portside outrigger. At its tip hangs the try net, a small net used for locating shrimp during 10-minute test drags (or “tries”). He puts out the try net, and when he hauls it back in shortly, out spill a dozen shrimp. They flip and vault over the deck, tiny legs treading air along the transparent shells. Several are sizable. Gilbert quickly winches out the main net (the otter trawl), moving from transom to cathead to pin rail, tying and untying ropes, lazy line and cables, stepping in a familiar dance with the gear.

Woven of green nylon cord with a 1 3/8 inch mesh, the otter trawl is 90 feet long and 38 feet wide at the bottom, 32 feet wide on top. The net precisely conforms to state regulations limiting mesh and net size for the bay for this time of year. In the byzantine universe of commercial fishing regulations, if this was September instead of June the net could be larger, but so must the mesh. That is, if he’s shrimping on his bay license instead of his bait license.

Gilbert watches the long net trail backward in the frothy wake, then finally drops the boards, two large slabs of steel shaped for their namesake. He shoves the throttle forward, the engine roars and vibrates, the prop boils up mud as the doors veer outward in the water like twin rudders spreading the mouth of the net. A long tickler chain connecting the boards bumps over the bottom mud where shrimp are burrowed down, causing them to leap upward for the net to scoop them inside.

The drag will last about 45 minutes, so Gilbert returns to the cabin and settles into the pilot’s chair for breakfast, a pint of chocolate milk and a packet of small sugar donuts. Not exactly health food, but easy to prepare. Meanwhile, he steers the boat along a serpentine route and listens to chatter on the marine band radio.

Working a boat alone, as Gilbert does, is unusual. It’s dangerous—fall overboard and it’s a long swim or a slow drowning—but deckhands are famously unreliable. They bum cigarettes and food, tend to drink and show up hung over, or simply don’t show.

“Plus I’m a cheap SOB,” he adds with a chortle. “I like to keep what I make.”

Even with a deckhand, the long hours on a boat on open water are isolating. The marine channel stays busy. If other shrimpers are coming up empty, they readily share the news; if they’re hitting shrimp heavy, they probably won’t mention it. Not even the most sociable want to share paydirt with a crowd.

After scarfing the final donut, Gilbert talks briefly on the radio, sympathizing with a fellow shrimper a mile away. He takes a call on his cell phone from his wife, Chris. The Gilberts recently leased the North End Bait Camp at Rollover Pass. Chris manages it and needs more live bait shrimp ASAP; he says he’s working on it. Hanging up, he describes the bait camp as an effort to diversify the family economy.

“I’m getting old, pardner. I can’t see working this boat when I’m sixty. I need to think ahead.”

The Gilberts also bought a home with an attached duplex apartment they rent short-term to sportsfishermen. A little here, a little there, he reasons, and it adds up. A shrimper covering his bills learns to scrabble.

He stubs out a cigarette, says, “Let’s haul in that net. I’d sure like to catch some and go in. Man, I’m still tired from yesterday.”

***

By noon, Gilbert is finishing his fifth drag and the trawler is broiling beneath a white-hot sun in a pale, blanched sky. The heat seems unyielding. The boat rocks, the engine drones, the pungent reek of fish and sour mud and diesel hangs over the slick deck. Even the shallow bay water registers 85 degrees Fahrenheit.

A sweating Gilbert winches in the trawl and raises the bag, loosens the bulging pocket over a tank. The catch falls with a whoosh and a splash. The pocket is retied, the net winched back out, the doors plunge beneath the surface for another drag.

Wiping his face with a forearm, Gilbert squints upward hoping for a cloud. Nada. He dips into the drop tank and lays part of the catch on the culling board: mullet, shad, silver ribbon fish with sharp teeth, small jellyfish (“sea wasps”), croaker, cigar minnows, crabs, robinfish, a mean-looking sting ray… and shrimp.

He slides the by-catch offboard into the bay, a thick flock of gulls screech and spar for anything dazed enough to float. Sleek black cormorants dive for what sinks, pelicans loaf for what’s overlooked, and magnificent pterodactyl-like frigatebirds circle high above, primed to dive-bomb unsuspecting gulls and pirate away a prize. For foraging birds, a shrimp trawler is a water-borne cafeteria.

The shrimp, unlike the by-catch, go into a second tank, then a third and a fourth, if necessary. Tank pumps circulate bay water in an effort to keep them alive. Live bait shrimp bring in twice the money of dead shrimp.

Gilbert keeps careful watch on his course while culling, steering the boat from a second wheel by the tanks, avoiding the crab traps marked with small white buoys dotting the bay. “A crab trap tearing up the net can sure ruin a day,” he allows.

He culls quickly, expertly, while commenting on the varieties of shrimp and their behavior, and the man-made laws governing shrimpers. None of it is simple.

Take the matter of spawning. Shrimp grow and thrive in the estuarine bays and marshes but they aren’t born there. Brown shrimp (Penaeus aztecus) spawn offshore in the Gulf in about 400 feet of water during winter months, while white shrimp (Penaeus setiferus) spawn in about 35 feet of Gulf water in the spring. (A third variety, the pink shrimp, isn’t found much this far north; it prefers the saltier water found in Texas bays further south.)

Once spawned, the larvae of all shrimp work their way back into the bays and marshes to grow. They are omnivores, feeding on smaller organisms living among the rich sediments and nutrients of the estuary. The brown shrimp then migrate en masse back into the Gulf during spring and summer, the whites wait until several months later. These differing spawning and migratory patterns result in complicated—and increasingly restrictive—regulations on when and how shrimpers work, aimed in part to ensure annual spawns aren’t disrupted.

Following the regulatory scheme, Texas bay shrimpers landed about 9.4 million pounds of shrimp in 2001. Almost half of that came from Galveston Bay, the most productive estuary in Texas and easily one of the most productive in the nation. Gilbert’s boat was one of 132 shrimp boats working Galveston Bay on May 15 this year, the opening day of spring bay season; a total of 182 boats were working other Texas bays.

On the other hand, Texas Parks and Wildlife figures show about 1,200 bay licenses currently in effect, and another 1,200 bait licenses. With a bait license there’s no closed season but the bag limits are much smaller and half the shrimp must be kept alive. Almost all bay shrimpers carry both licenses so they can work year round, though winter takes are small.

The numbers indicate most bay shrimpers, unlike Gilbert, are part-timers holding other full-time jobs. A license is tied to the boat, not the shrimper, and the state is issuing no new ones. In fact, the state is buying back bay licenses—25 percent of them have been “retired” since 1995—to increase each remaining shrimper’s slice of the total pie. At least theoretically.

Gilbert shrugs, grins, offers his machine gun laugh. In his view, there’s still too many bay boats. And the shrimp are being depleted. Though it isn’t the shrimpers’ fault, he says. Estuary degradation caused by loss of wetlands to developers—the Houston Metroplex now overruns the northern and western stretches of Galveston Bay—as well as urban runoff, industrial pollution, and agribusiness pesticides and herbicides all conspire to hurt the shrimp.

And what hurts the shrimp hurts the shrimpers.

Still, unregulated global trade is putting the biggest economic hurt on Texas shrimpers, including offshore Gulf shrimpers who annually land three times the catch of bay boats. Imported pond-raised shrimp from cheap labor markets in Asia and South America are, says one Parks and Wildlife official, “killing our shrimpers.” The imports don’t taste as good as wild shrimp, and some have been found laced with animal antibiotics detrimental to human consumption, but about 85 percent of the shrimp consumed in the U.S. is imported. Some argue it all should be imported. Texas shrimpers feel beleaguered from every side.

“Personally, I think they’ll close the bays to commercial shrimping within ten years,” Gilbert observes. “They’re already trying. They’ll make sportsfishermen go to artificial bait. Right now, if you aren’t selling live bait, you can’t make a living. Price on food shrimp barely covers your operating costs.”

***

By 2 p.m., the trawl net on the Stingaree 2 is out of the water, pursuant to state regulations for bay shrimpers from May 15 to July 15. Gilbert is beat. The wind has died, the sun is a searing torch, the pilot house has become a sauna. Gilbert is cruising homeward to off-load the day’s catch: six gallons of live shrimp, about 40 pounds of dead. It’s not even close to a limit.

“An average day,” he observes, “which ain’t good. Haven’t had a really good day in a while. We’ve had three, four bad years in a row.”

Once docked, he’ll do some maintenance, repair a clutch seal. He lights a cigarette, leans back in the pilot’s chair—the captain’s chair, really—and pops the tab on a cold soda. He closes one eye, calculating.

“Add and subtract it all,” he finally announces, “I’m making minimum wage.”

He wags his head and lets go. The laughter rockets through the small cabin: a working man’s commentary on the absurdity of it all—chasing those shrimp, trying to catch them, what happens when you do, or don’t, in a world mostly beyond your control.

*****