[Note from Christopher: I think Caddo Lake in northeast Texas is one of the most beautiful places on the planet. And strangely enough, not that many people know about it. A few years ago, they also didn’t know about an unusual boat plying the lake’s water, a 19th century-style paddlewheel steamboat. So I decided to write about that boat and the lake, too. This article ran in Texas Co-op Power Magazine in 2000. If you look at the next article in this Magazine section of the website, you’ll find a short accompanying sidebar I wrote about a very different kind of boat also working Caddo Lake, Billy Carter’s Go-Devil.]

As Mark Twain tells it in his Life on the Mississippi, when he was a boy there was but one ambition among his friends, to become a steamboatman. “So by and by,” he wrote, “I ran away.”

A century later, a young woman in Tyler shared a similar dream and the same impulse to give it substance. Lexie Palmore, then in her early twenties and in possession of a master’s degree in art, had never been the sort to vie for a slot as a Tyler Rose Festival debutante. Lexie was sure the world was larger than East Texas, and she loved boats. So by and by, she headed for the Mississippi.

As with Twain, who cribbed a lowly position in steerage on his first effort, Lexie’s career began modestly. She worked as a maid in housekeeping on the Delta Queen, a majestic riverboat 285 feet long. And like Twain, no matter how mundane her official duties, she kept ending up in the pilothouse pelting the helmsman with questions, just itching to get her hands on the wheel.

Twain left the boats and went on to write about his stint as a river pilot, but Lexie—now Lexie Palmore McMillen—really never quit. Three decades later, she holds more inland waterways pilot’s and master’s licenses than any woman in the country. She has piloted the Delta Queen and the even larger (at 385 feet) Mississippi Queen. And she is the captain of her own paddlewheel steamboat.

Granted, at 50 feet in length, the Graceful Ghost may seem like a minnow against the whale-sized proportions of the great Mississippi riverboats. But then, Caddo Lake isn’t exactly the Great Father of Waters, either.

***

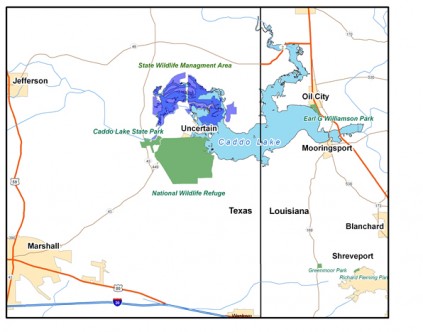

Caddo Lake is breathtaking all the same, a magnificent body of water in its own insular and mysterious way. Straddling the Texas-Louisiana line east of Jefferson, in the outlaw borderlands once claimed by both Spanish and French, it is a waterborne forest of towering bald cypress draped in Spanish moss, an interlocked labyrinth of shallow open lakes and narrow connecting boat roads, of bayous and shadowed backwaters and silent oxbows within the cypress brakes, of slender channels snaking through vast aquatic fields of floating green pads starred by delicate white and yellow blooms: water lilies, spatterdock, and the glorious yonqupin, otherwise known as the American lotus.

Depending on how (and where) you see it, Caddo Lake is either river or delta swamp or open lake. Its size is in dispute because no one is certain just where it should begin upstream along its feeder bayous, Big Cypress and Black Cypress and Jeem’s Bayou among others. But most agree that measuring has to stop at the dam below Mooringsport, Louisiana. So it’s safe to say that Caddo Lake is somewhere between 25,000 and 33,000 acres in size.

It’s also safe to say where the lake got its name. Two confederations of Native American tribes living in this region were known as the Caddo Nation. Peaceful hunters and fishermen, farmers and traders, the Caddos virtually disappeared under the onslaught of European settlers, but not before passing along their word for friends, teychas. The Spaniards pronounced it tejas. In good time, it became the name Texas. And the Caddos left their own name to the lake.

But try to assert how Caddo Lake got its start and you’re in for another dispute. The Caddos were content with a legend. A great chief had a vision in which the lands were flooded, so he moved his people upland to an area now occupied by Caddo Lake State Park. And the flood did come, as predicted. A good story, but not science. So some old-timers claim the lake was formed by the great earthquakes of 1811-1812 which centered on New Madrid, Missouri, to the north. But most agree the lake resulted from the Great Raft of the Red River, a natural log jam 150 miles long near present day Shreveport. The jam backed up water into the Big Cypress watershed, forming Caddo Lake.

Whatever the cause, the result was the largest “natural” lake in Texas, a place of almost unsurpassable beauty. It has had more than one incarnation. When the Red River Raft was cleared in the late 1800s, Caddo virtually disappeared. It became swamp. Then oilmen discovered the big Louisiana field in the early 1900s and lobbied for a dam so they could float their drilling equipment in. The dam was built, the lake reappeared. Its various parts reveal by name its colorful history of settlers, outlaws, bootleggers, and poachers: Hog Wallow, Whangdoodle Pass, Jack Daddy Pocket, Government Ditch.

Nowadays, fishermen come casting the waters, and duck hunters appear during winter. And eco-tourists come year-round to luxuriate in the wildlife inhabiting the dappled surface and the moist air hovering above it. They find beaver, otter, blue herons, great egrets, alligators, and a galaxy of roaring frogs.

They also find the Graceful Ghost, which Lexie Palmore McMillen, along with her husband Jim McMillen, operate as an excursion boat based on Taylor Island in the little town of Uncertain.

***

Sitting near the boat dock, beneath a canopy of shade trees, Lexie tells how she got from here. She is a tall, fair-skinned woman with short blonde hair going gray. She dresses comfortably and walks with an outdoorsman’s carriage but wears a cell phone on her belt. Calls come in regularly from folks asking about the 90-minute excursions onto the lake or arranging a charter, and she’s ready. The boat operates late March through November, except for Sundays, church day, and the sunset excursion is a favorite.

She speaks softly, going back to her time on the Delta Queen, when she asked to steer the boat “just to say I had”. Fortunately, they let her. “And I did it more and more,” she recollects. “Well, it seemed like all their pilots were getting older, ready to retire, and a company guy suggested I go to the National River Academy in Helena, Arkansas, to learn piloting. So I did.”

Lexie spent two years at the school, alternating classes with work on the steamboats, and she earned a mate’s license. “The mate’s second in command, in charge of the deck crew, maintenance and handling lines,” she explains. “It’s not hard work, but I didn’t like it much. I wanted to be a pilot.” Mark Twain had once expressed the same yearning when he wrote, “Pilot was the grandest position of all.”

So it was back to school, along with two years of pilot training aboard a boat. “Then you can take the test. You have to know the rules of the road and navigation. You have to draw the river by memory.” That means knowing each underwater and highwire crossing, mile markers, bridges, locks and dams. “And you have to know each of them to the tenth of the mile.”

Lexie pauses to let the utter magnitude of that requirement sink in, then says, “I eventually got a first class license for piloting 1,750 miles of the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee rivers.”

She strokes her orange tabby, Puddy, and glances over at her husband Jim, who is working on the wood-fired boiler of the boat. He is from Wyoming, not a place known for birthing mariners. But he was a Navy officer in Vietnam, and after earning a university degree in English he moved to Clear Lake on the Texas coast. He developed his shipwright skills and taught at a maritime school in Houston, eventually qualifying for a Coast Guard license as a Master of Steam and Motor Vessels. By the time Lexie and he met, she had acquired her own Unlimited Inland Master’s License.

You might say the two of them know boats. And you might say they are eminently qualified to navigate a waterway. A good thing, too, as Caddo Lake is no ordinary waterway.

“It can be challenging,” Lexie admits, “because of all the trees out there you have to slither through. Plus the stumps. And the wind blowing.” The double-decker Graceful Ghost has a flat bottom so requires a lot of ballast for steady steerage. They use concrete blocks and lead, and three 55-gallon drums of water for the boiler. The boiler itself weighs 1,000 pounds. The ride is solid.

And she knows the lake. Though it changes day to day, year to year, she sees those changes as they occur. Lexie says she has read Twain’s Life on the Mississippi, in which he wrote, “The face of the water, in time, became a wonderful book.”

***

Lexie, like Jim, is a quiet person. It takes a while to learn that she eventually left the Mississippi steamboats to pursue her love for painting. She’d tried that once before, right out of college. “I’d kind of hung out my shingle for art work,” she says with a small smile, “but it seemed like I was doing a lot of sign painting.” Only this time she persisted. Based in Tyler, she also spent time scuba diving and doing volunteer work on the schooner Elissa docked in Galveston. And she devoted time to helping archeologists try to locate the sunken remains of the Mittie Stephens, a riverboat that went down in Caddo Lake in 1869 with a hundred people aboard.

The Mittie Stephens was one of hundreds of steam-powered riverboats that plied the waters of Caddo Lake from the Red River all the way up to Jefferson, then the second largest port in Texas, during the 1800s. The cotton plantations and demand for goods kept the steamers busy until the double whammy of the Red River Raft destruction and the Confederate defeat ended plantation culture in northeast Texas. The lake became calmer, and the Mittie Stephens slowly settled into the lake bed.

Lexie and the archeologists never found the remains, but the search moved her to nearby Jefferson during the mid-1980s, where she painted and occasionally piloted one of the local excursion riverboats based on Big Cypress Bayou. That’s where she would eventually meet Jim, who also was piloting.

“I had a little steam launch back then,” Lexie recalls. “Twenty-six feet long, propeller driven, named Willie after Steamboat Willie, the Mickey Mouse character.” But she was interested in a larger boat and found a design in a catalog for a traditional 19th century riverboat. “They built a lot of these boats back then and shipped them in pieces to countries in South America where they didn’t have the technology to do it.”

She located a ship’s carpenter, Joe Babcock, downstate near Plantersville. Then she got cold feet. “Because of the money,” she says. “But Joe talked me into it. It took a long time to build, about one and a half years. He did between other jobs and me getting the money to pay.” The initial cost came to about $50,000. “Of course,” she muses, “if I’d have waited a little longer, Jim could’ve built it.”

Still, she had a beautiful riverboat. Fifty feet long and 12 feet wide “over the deck”, with a draw of 20 inches. Two 10-horsepower engines with horizontal pistons 16 inches long were located aft to turn the paddlewheel, with a smokestack behind the pilothouse and a three-chime whistle. “It’s historically accurate,” Lexie says, mama-proud.

She named it the Graceful Ghost after a piano rag she’d heard. The words and music are framed and hang on the main deck. “It’s a real pretty piece,” she adds. “It seems to fit.”

***

There are at most a dozen or so excursion steamboats in the nation. Lexie says the Graceful Ghost is the only one in Texas “as far as we know.” She and Jim brought the boat from Jefferson to Taylor Island on Caddo Lake in 1993 because they loved the place. Also, it seemed the boat fit the lake and there would be people eager to take excursions in it. They were right on both counts. It’s a very quiet ride and a good way to view Caddo.

Unless they’ve been out earlier in the day, they fire up the boiler a couple of hours before an excursion. The engines and boiler are efficient. They burn scrap wood, and an armful powers the steamboat for the hour and a half trip.

Leaving the dock before sunset, the paddlewheel churns water astern and the twin escape pipes rising in back above the top deck whisper and sigh like the breath of a sleeping dragon. On the lower deck, passengers sit or walk about and watch the boat machinery at work. Topside, beneath an awning, cushioned benches face port and starboard for convenient viewing of the passing scenery. Lexie and Jim take turns at the wheel and explain the ecology and history of the lake.

The boat slips from beneath the cypress trees and into a lane between the deep green flowering pads enveloping the surface. A night heron wings overhead, and the lake to either side passes back into cypress brakes drenched in Spanish moss and unseen shores. Crickets and cicadas hum, the chorus of frogs begin their evening song. It is not hard to imagine one is in church, a great natural temple celebrating the sanctity of life.

And so the passengers murmur, or soon fall silent, as the Graceful Ghost quietly glides into the embrace of Caddo Lake, with Captain Lexie Palmore McMillen at the helm. Pilot and navigator, her gaze sweeps the everchanging lake. She reads it like a book.

*****