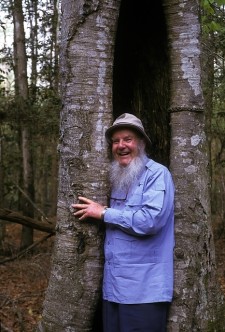

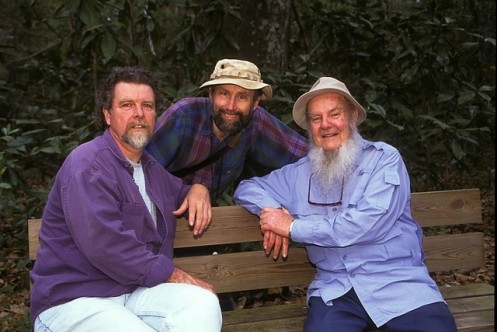

[Note from Christopher: Howard Peacock is an extraordinary man and a great friend. A life-long eco-activist and fellow writer, he helped create the Big Thicket National Preserve in East Texas after years of battling the big multinational timber companies and backward-thinking Texas politicians. On a lovely spring day in 2000, the two of us took a long walk in the Preserve along the Kirby Nature Trail north of Kountze. This resulting article was published in the March 2000 issue of Texas Co-op Power Magazine, whose editors have graciously permitted me to re-publish it here. Another fine friend, the gifted professional photographer Randy Mallory of Tyler, Texas, took these lovely photos to illustrate the piece. By the way, I am glad to report that Howard’s lament regarding the Preserve having no Visitors Center has since been rectified. It now has one, and it’s terrific.]

“Man can find deep solitude and, under conditions of grandeur that are startling, come to know himself and God.”

—Former U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas

We’re strolling along a trail beneath a canopy of beech, the path mottled with sunlight, our feet padding a soft carpet of leaves. The early spring air smells sweet with leaf-burst and wildflowers. My companion, Howard Peacock, stops and cocks an ear.

“That’s a red-eyed vireo.”

I listen closely. A series of short caroling notes, flute-like, bounce through the morning woods. My first thought: I’ve been hearing that bird all my life and had not an inkling of its name.

But that’s how it is on a walk through the Big Thicket of East Texas with Peacock, a naturalist and writer who lives in Woodville. You begin thinking you know something because you can identify half a dozen trees, a few wildflower species and a handful of bird calls. After a while, you discover what you really know: hardly anything at all.

It’s doubly humbling to learn that Peacock, 75, is trying to forget what you never knew anyhow. Standing before a tree I identify as either crepe myrtle or ironwood, he says, “It’s hornbeam. But ironwood is a common name for hornbeam. And there’s another tree called ironwood. And that other tree also is called hawthorn beam. That’s where you get into trouble.

I nod, understanding completely.

“Another common name for this tree is muscle tree,” he continues, pointing to the hornbeam, “because the convolutions in the trunk look sort of like muscles. Common names are very interesting but they are not very precise.”

I nod again, thinking, Geez, is he ever right about that. Then he strokes his beard and lowers the boom.

“I am trying to forget names of trees and flowers and birds and everything like that. I’ll tell you what I found out. I found out that the names get in the way. When you are looking at a flower and trying to figure the name, you are not enjoying the flower. I am trying to forget all that.”

The attitude seems very Zen to me—“Don’t let mental concepts pollute clear perception”—and I feel a tad like Grasshopper has just received his weekly kung-fu lesson from Master.

But mostly I’m relieved. There are at least 85 species of trees in the Big Thicket, and more than 1,000 species of shrubs and flowering plants, and 300 species of birds. Now I don’t have to learn them all. Not only that, but I will be wiser for my ignorance.

Then I turn toward Peacock and see him gazing beatifically at the hornbeam. I’m standing here noodling in my head, he’s experiencing the tree. Boy, do I feel dumb.

Howard Peacock is a man who puts a premium on joy. And one reason he finds for rejoicing is that a group of stubborn, organized activists—of which he was one—managed to save the 86,000 acres in East Texas known as the Big Thicket National Preserve.

The preserve is a collection of 12 units along the Neches River bottoms north of Beaumont and scattered among water corridors to the west toward the Trinity River. Established in 1974, the preserve was officially designated an international Biosphere Reserve by the United Nations in 1981. As a unique ecosystem, it ranks in an elite world-class category.

Here in Texas, Big Bend and Palo Duro Canyon get better press in a state entranced with its western cowboy mythos, but the Big Thicket is arguably the most extraordinary landscape in the state, bar none.

The geologic story of this region involves glaciers and repeated ice ages and rising and retreating seas. The land once was roved by woolly mammoths. But the first telltale human signs appeared about 7,000 years ago, and the Native Americans who later came to reside in East Texas called the region the “Big Woods.”

And it was. More than 3.5 million acres in all, the primitive Big Thicket ranged from the Sabine River westward to present-day Navasota, from Beaumont northward to near Lufkin, an area of more than 5,500 square miles where average annual rainfall exceeds 55 inches. The early Spaniards mostly went around it, but a century and a half later, during the 1830s, Anglos drifting westward from the American South began to penetrate the dense region they came to call the “Big Thicket.”

Legend says that name was derived from the impassable thickets of titi, an Indian word for the shrubs that grew so thickly a snake could hardly thread them. That’s where Confederate draft evaders went to hide during the Civil War, where Confederate troops tried to burn them out.

The Big Thicket region, as with all of East Texas, was logged heavily after the Civil War. The timber was sent eastward and northward for a nation reconstructing itself and extending railroads into the frontiers. The heavy logging continues; timber is the number one agricultural industry in East Texas.

Today, only a few slivers of virgin woods remain, and those are within the Big Thicket National Preserve. With its 10 overlapping ecosystems, from eerie cypress sloughs to pine forests, the preserve is known to scientists as the “Biological Crossroads of North America.”

No wonder this remarkable place also is called “America’s Ark,” with all the environmental implications that name entails.

The story behind the preserve—how it came to be established by federal law despite decades of opposition—is almost as complex as the landscape. Or as the intricate journey of Howard Peacock’s life.

As we walk along the Kirby Nature Trail in the Village Creek bottomlands, not far from the preserve’s visitors station north of Kountze, he spins the interweaving tale in a long, casual narrative interrupted by commentary on the passing scene and suspended moments of silence. Stopping to marvel at an enormous magnolia or the fragrance of blossoming jessamine, he seems much the pilgrim who has traveled far to honor a holy place.

But he is not religious, Peacock says, not in conventional terms. “I am spiritually oriented.” The basis of his beliefs? “Kindliness and good humor and tolerance. Playfulness,” he replies.

He pauses to tug at his hat brim, the clear gray eyes searching the woods beneath bushy eyebrows that arch like a tomcat. He smiles. “I really enjoy playfulness.”

On the other hand, he has little patience for those who disrespect Mother Nature. “I cut off Exxon after the Valdez oil spill,” he says. “Haven’t bought a gallon of their gasoline since. The company used such poor judgment.”

That was a decade ago, but the attitude runs through the current of all his years, from the time he was a Cub Scout in Beaumont to the present. In the Navy during World War II, he loaded ammunition aboard ships in the Philippines. Later, he worked as a newspaper journalist, then as editor of the Houston Chamber of Commerce weekly and for the Southern Pacific Railroad magazine. Eventually he became director of the United Fund—precursor of the United Way—in Houston.

“All that time,” Peacock says, “I was free-lance writing for magazines,” a constant in his otherwise zig-zag career. The other constant: taking to the woods when possible and joining the ongoing battle to create a national preserve in the Big Thicket.

“The first movement began back in the late 1920s. The Depression came along and hurt it. Then World War II came along and just about killed the movement. But it revived in the late 1950s and 60s.”

By then Peacock was leading the Texas Bill of Rights Foundation, which he’d help found with friends. The John Birch Society was flexing its muscle, President Kennedy was assassinated. “This was a time of very serious hostility between opposing political factions,” he recalls grimly. “Our group wanted to create a forum for these differing ideas to be presented in a reasonable atmosphere.”

For seven years, the Houston-based foundation held town hall meetings and public school programs, even broadcast a weekly TV show on which public figures as diverse as Richard Nixon and Robert Kennedy appeared.

Meanwhile, Peacock had become increasingly active in the Big Thicket Association, formed in the 1950s to continue the long struggle to preserve some of the East Texas wilderness. The names of those involved in the movement roll off Peacock’s tongue: Lance Rosier, Archer Fullingim, Geraldine Watson, Pete Gunter, Maxine Johnston, Billy Hallmon, and others. They, in turn, nicknamed him “Tush Hog,” a term usually reserved for the toughest ol’ rooter in the woods.

“They were my soul buddies,” Peacock fondly recalls. “It was a very exciting time.” He had moved to a job at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, where he put on programs about the Big Thicket. “And on weekends I was over here taking groups to places like this,” he adds, sweeping an arm toward the lush bottomlands.

The determined activists drummed up support among scientists and nature writers, and took their battle public through state and national media. Among the high-profile advocates of the preserve was U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, a strong supporter of natural preservation. But the movement faced even stronger opposition among a group that wielded tremendous political influence in East Texas—the timber companies.

According to Peacock, it took two unusual men to finally bridge the gap. Ironically, one of them was a life-long timberman.

“The guy who really turned the trick was Arthur Temple,” Peacock says. “There was a complete standoff—I mean a hostile standoff—between the environmentalists and the timber companies. Then Arthur Temple broke the pattern.”

The board chairman of Temple Industries—along with Kirby and Louisiana-Pacific, one of the big three timber companies then—Arthur Temple appointed one of his foresters, Garland Bridges of Jasper, to work with the eco-activists and look for a compromise. Meanwhile, Temple worked on his fellow timber executives, convincing them it served the public interest to preserve parts of the Thicket. In the end, an agreement was reached.

“We didn’t get the 300,000 acres we desperately wanted,” Peacock admits, “but we got about 85,000. That at least preserved some of the ecological systems in the Thicket.”

The agreement still needed passage through Congress, and the man who had laid the groundwork for that was U.S. Senator Ralph Yarbrough. “He was our champion in the Senate,” Peacock says. “He was a great man.”

For years, Yarbrough—with the help of U.S. Rep. Bob Eckhardt—had kept the idea of a national preserve alive in Congress despite intense opposition from timber interests. The legislative wrangling continued right up to the end, when Yarbrough was no longer a Senator, but a final bill was passed and signed into law October 11, 1974.

Even then, there was work yet to do. “The acquisition of the land, for one thing,” Peacock notes, “and then the plans for a proper visitors center, which still have not come to fruition.”

The land for the preserve eventually was acquired with minimal conflict—most belonged to timber companies or absentee owners, Peacock says—and is managed by the National Park Service. Attempts to expand it another 11,000 acres have been stymied since 1993, when Congress passed approving legislation. Negotiations to swap National Forest Service land for the additional preserve, which is owned by timber companies, have faltered.

Peacock hopes the land eventually will be acquired, but the nonexistent visitor center rankles him. “The center is supposed to have movies, big pictures, exhibits, all that good stuff you see at any national park.” He notes that the facility would bring more visitors and raise the visibility of this precious part of Texas. It would benefit both the park and the area economically.

So why, after 26 years, hasn’t the center been built? “Money,” Peacock replies. He laughs wryly. “But maybe the political landscape will change.”

If such a center existed, Peacock described the Big Thicket it would interpret in his 1994 book Nature Lover’s Guide to the Big Thicket (Texas A&M Press). On page after page, he describes the 10 complex ecosystems of the preserve, from baygalls to longleaf pine uplands to oak-gum floodplains. Found in them are cacti and orchids, four species of carnivorous plants, splendid ferns, champion trees and mushrooms, minks and bobcats and alligators.

What strikes any visitor to the preserve is that one moment you seem to be moving through the Amazon jungle, yet a short time later you are wandering through a forest of upland pines. The biological range is phenomenal. “The Thicket contains more kinds of ecosystems than any other place of similar size in North American, perhaps in the world,” Peacock observes.

It is extraordinary to think that this exotic and fantastic ecological mix once covered an area of Texas larger than the state of Connecticut. And it is sobering to think that although some of it was saved, more than 97 percent of it was lost. Does that make Peacock feel his cause was a failure?

“No, it was a success,” he quickly replies. “Not a huge success. We didn’t get all the ecological treasure, but we got some nice pieces of it. We got pieces we can work with.”

That any of it was saved, and that he played a role in the saving, seems something of a miracle to him. And a reason to reflect. “Yes, it was one of the best times of my life,” he recalls thoughtfully, “one of the best times.”

Then Peacock suddenly stops and that familiar look of joy passes over his face. “Just look,” he exclaims, pointing, “look right there. I will tell you one thing I had not expected to see, and that is Jack-in-the-pulpits coming up.”

I lean forward and see the tall green stems rising from the forest floor, the peculiar canopy atop each stem, and mentally note to remember the color, the shape, the name of this graceful flower.

But I will soon forget, I just know it.

Still, I also know that I can always come back and see it again. Maybe someday I will bring my grandchildren, if we are lucky. I will show them the flower and explain that I once knew its name but wisely forgot it so that I could see it all the better, on the advice of the happy man who first showed it to me.

*****

![ala-coush.res.dancers.mac[1]](https://www.christopher-cook.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/ala-coush.res_.dancers.mac1_.jpg)

![woodville-indian-chief-1[1]](https://www.christopher-cook.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/woodville-indian-chief-11.jpg)