[Note from Christopher: I won’t say much about this piece, as it is self-explanatory. Call it an encomium, a memorial tribute. And suffice to say it’s about the man who is largely accountable for how I ended up living in Prague, Czech Republic. The piece was published in several newspapers and journals, including The Prague Post in the Czech Republic and The Progressive Populist in the U.S.]

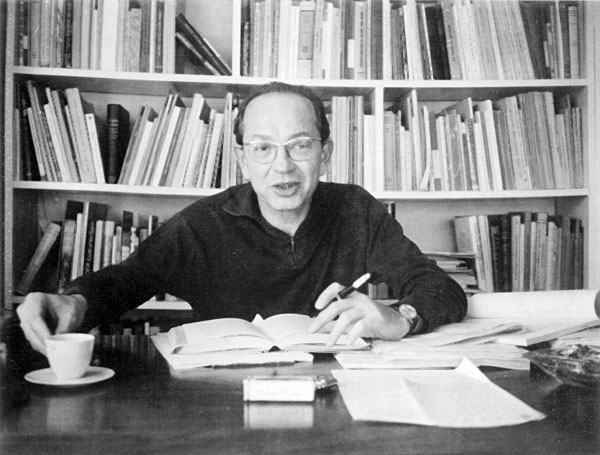

Jiří working in his Paris apartment, circa 1970s.

PRAGUE, Czech Republic — July 28, 2011

We buried Jiří’s ashes today. On a warm summer afternoon, in a cemetery under ancient trees. After all these years, he’s come home.

It was not an easy journey, or a short one. He fled Prague in 1948, escaping on foot over the mountains into Austria, one step ahead of the communist purges. There followed 63 long years in exile, in Paris and New York, living two lives under a double identity.

When I first met him in Paris in 1994, he was known as Paul Barton, an unlikely name for a Czech. He worked for the European office of the AFL-CIO and was planning to retire soon. In his 70s, he was not well. He smoked heavily, loved French wine and good food. His humor was ironic, the laugh wicked. I’d been brought aboard from the United States as his apprentice and replacement.

He apparently took a shine to me, a young man abroad for the first time, eager to learn, and soon after we became acquainted, he told his real name: Jiří Veltruský. Then, in bits and pieces, he told me his story.

As a university student in Prague, he’d been forced to leave school as the German occupation led up to World War II. He was later put to work in a weapons factory, where he became an underground trade union activist and member of the resistance movement, one of those Czech workers prone to sabotage who became a thorn in Hitler’s side.

When the war ended, Jiří returned to Charles University to finish his PhD in the philosophy of aesthetics—semiotics—with a special interest in theater. He became an assistant professor and member of the Prague Circle, a group of intellectuals, as well as a democratic activist.

All that came crashing down in 1948 when Stalin’s Russia made its final move on Central and Eastern Europe. Those Czechs who’d participated in the resistance and trade unions—in fact, anyone advocating western-style democracy—served as fodder for show trials, executions, prisons and labor camps. Jiří just barely escaped into Austria and made his way to Paris. His sole possessions were the clothes he wore and a book by the philosopher Edmund Husserl.

In Paris, he became a freelance journalist. Those were heady years, full of poverty and intrigue. He made weekly broadcasts to Czechoslovakia for Voice of America and Radio France. He wrote articles and books, served on a commission reporting on the concentration camps in the USSR. After using several pseudonyms, he finally settled on “Paul Barton,” a name suitable in French, English and German.

In 1962, Paul Barton moved to New York City as a representative of the Brussels-based International Confederation of Free Trade Unions. He focused on economic policy and human rights at the United Nations. Those were dramatic years, too, full of high aspirations and hard work. And, finally, a regular paycheck.

After 1968, when he returned to Paris to run the AFL-CIO’s European office, he resumed his career as a philosopher, and thereafter led a double life. By day, he was Paul Barton, trade union activist. Nights and weekends, he was Jiří Veltruský, a highly respected and much published scholar in the field of semiotics and theater. Few in the labor movement ever learned of this second life.

The first time Jiří invited me to his apartment, I saw walls lined with bookshelves overflowing with books. The classics of literature, in French, English and Czech. I saw hundreds of books on philosophy and semiotics, on drama and theater, all worn from constant use. It was there, too, that I met his charming wife, Jarmila, another Czech who’d lived for decades in exile.

At Jiří’s and Jarmila’s urging, I visited Prague in 1994 and immediately fell in love with the city. The atmosphere was vibrant, still teeming with energy just five years after the Velvet Revolution. I returned to Paris with a much larger understanding of the world.

Jiří died shortly after from a bad fall down the stairwell in his apartment building. Jarmila was heartbroken. She and I became closer, and I learned even more about the remarkable life of the man known as both Paul Barton and Jiří Veltruský, whose ashes then rested in a funeral urn on the mantel.

I eventually left Paris and moved to Mexico. But upon returning to Europe in 2001, I made Prague my home. Jarmila visits often; we remain close friends. So when she came to Prague bearing Jiří’s ashes, she asked me to the ceremony at the cemetery of the Brevnov Monastery.

There, today, we laid Jiří Veltruský to rest.

His exile was long, the journey even longer. But finally, he’s come home.

*****